https://theconversation.com/could-consciousness-all-come-down-to-the-way-things-vibrate-103070

Why is my awareness here, while yours is over there? Why is the universe split in two for each of us, into a subject and an infinity of objects? How is each of us our own center of experience, receiving information about the rest of the world out there? Why are some things conscious and others apparently not? Is a rat conscious? A gnat? A bacterium?

These questions are all aspects of the ancient “mind-body problem,” which asks, essentially: What is the relationship between mind and matter? It’s resisted a generally satisfying conclusion for thousands of years.

The mind-body problem enjoyed a major rebranding over the last two decades. Now it’s generally known as the “hard problem” of consciousness, after philosopher David Chalmers coined this term in a now classic paper and further explored it in his 1996 book, “The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory.”

Chalmers thought the mind-body problem should be called “hard” in comparison to what, with tongue in cheek, he called the “easy” problems of neuroscience: How do neurons and the brain work at the physical level? Of course they’re not actually easy at all. But his point was that they’re relatively easy compared to the truly difficult problem of explaining how consciousness relates to matter.

Over the last decade, my colleague, University of California, Santa Barbara psychology professor Jonathan Schooler and I have developed what we call a “resonance theory of consciousness.” We suggest that resonance – another word for synchronized vibrations – is at the heart of not only human consciousness but also animal consciousness and of physical reality more generally. It sounds like something the hippies might have dreamed up – it’s all vibrations, man! – but stick with me.

All about the vibrations

All things in our universe are constantly in motion, vibrating. Even objects that appear to be stationary are in fact vibrating, oscillating, resonating, at various frequencies. Resonance is a type of motion, characterized by oscillation between two states. And ultimately all matter is just vibrations of various underlying fields. As such, at every scale, all of nature vibrates.

Something interesting happens when different vibrating things come together: They will often start, after a little while, to vibrate together at the same frequency. They “sync up,” sometimes in ways that can seem mysterious. This is described as the phenomenon of spontaneous self-organization.

Mathematician Steven Strogatz provides various examples from physics, biology, chemistry and neuroscience to illustrate “sync” – his term for resonance – in his 2003 book “Sync: How Order Emerges from Chaos in the Universe, Nature, and Daily Life,” including:

- When fireflies of certain species come together in large gatherings, they start flashing in sync, in ways that can still seem a little mystifying.

- Lasers are produced when photons of the same power and frequency sync up.

- The moon’s rotation is exactly synced with its orbit around the Earth such that we always see the same face.

Examining resonance leads to potentially deep insights about the nature of consciousness and about the universe more generally.

Sync inside your skull

Neuroscientists have identified sync in their research, too. Large-scale neuron firing occurs in human brains at measurable frequencies, with mammalian consciousness thought to be commonly associated with various kinds of neuronal sync.

For example, German neurophysiologist Pascal Fries has explored the ways in which various electrical patterns sync in the brain to produce different types of human consciousness.

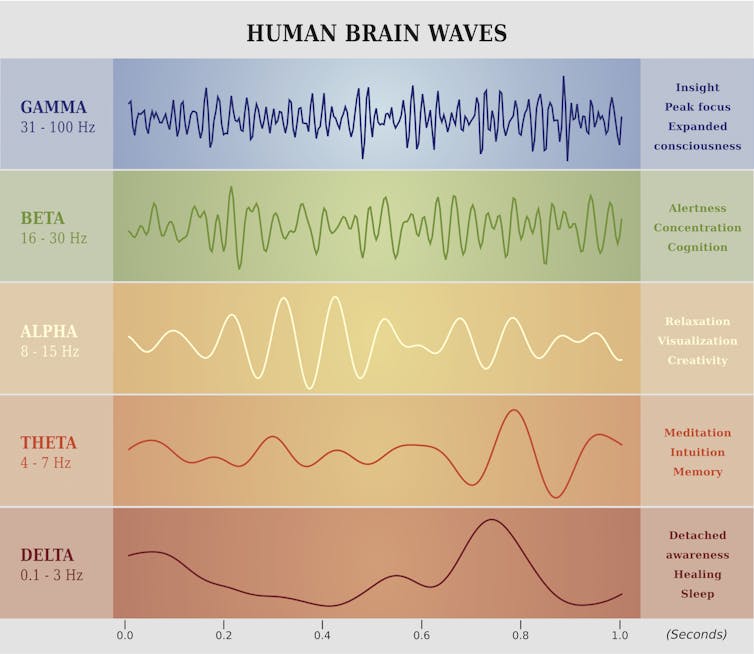

Fries focuses on gamma, beta and theta waves. These labels refer to the speed of electrical oscillations in the brain, measured by electrodes placed on the outside of the skull. Groups of neurons produce these oscillations as they use electrochemical impulses to communicate with each other. It’s the speed and voltage of these signals that, when averaged, produce EEG waves that can be measured at signature cycles per second.

Gamma waves are associated with large-scale coordinated activities like perception, meditation or focused consciousness; beta with maximum brain activity or arousal; and theta with relaxation or daydreaming. These three wave types work together to produce, or at least facilitate, various types of human consciousness, according to Fries. But the exact relationship between electrical brain waves and consciousness is still very much up for debate.

Fries calls his concept “communication through coherence.” For him, it’s all about neuronal synchronization. Synchronization, in terms of shared electrical oscillation rates, allows for smooth communication between neurons and groups of neurons. Without this kind of synchronized coherence, inputs arrive at random phases of the neuron excitability cycle and are ineffective, or at least much less effective, in communication.

A resonance theory of consciousness

Our resonance theory builds upon the work of Fries and many others, with a broader approach that can help to explain not only human and mammalian consciousness, but also consciousness more broadly.

Based on the observed behavior of the entities that surround us, from electrons to atoms to molecules, to bacteria to mice, bats, rats, and on, we suggest that all things may be viewed as at least a little conscious. This sounds strange at first blush, but “panpsychism” – the view that all matter has some associated consciousness – is an increasingly accepted position with respect to the nature of consciousness.

The panpsychist argues that consciousness did not emerge at some point during evolution. Rather, it’s always associated with matter and vice versa – they’re two sides of the same coin. But the large majority of the mind associated with the various types of matter in our universe is extremely rudimentary. An electron or an atom, for example, enjoys just a tiny amount of consciousness. But as matter becomes more interconnected and rich, so does the mind, and vice versa, according to this way of thinking.

Biological organisms can quickly exchange information through various biophysical pathways, both electrical and electrochemical. Non-biological structures can only exchange information internally using heat/thermal pathways – much slower and far less rich in information in comparison. Living things leverage their speedier information flows into larger-scale consciousness than what would occur in similar-size things like boulders or piles of sand, for example. There’s much greater internal connection and thus far more “going on” in biological structures than in a boulder or a pile of sand.

Under our approach, boulders and piles of sand are “mere aggregates,” just collections of highly rudimentary conscious entities at the atomic or molecular level only. That’s in contrast to what happens in biological life forms where the combinations of these micro-conscious entities together create a higher level macro-conscious entity. For us, this combination process is the hallmark of biological life.

The central thesis of our approach is this: the particular linkages that allow for large-scale consciousness – like those humans and other mammals enjoy – result from a shared resonance among many smaller constituents. The speed of the resonant waves that are present is the limiting factor that determines the size of each conscious entity in each moment.

As a particular shared resonance expands to more and more constituents, the new conscious entity that results from this resonance and combination grows larger and more complex. So the shared resonance in a human brain that achieves gamma synchrony, for example, includes a far larger number of neurons and neuronal connections than is the case for beta or theta rhythms alone.

What about larger inter-organism resonance like the cloud of fireflies with their little lights flashing in sync? Researchers think their bioluminescent resonance arises due to internal biological oscillators that automatically result in each firefly syncing up with its neighbors.

Is this group of fireflies enjoying a higher level of group consciousness? Probably not, since we can explain the phenomenon without recourse to any intelligence or consciousness. But in biological structures with the right kind of information pathways and processing power, these tendencies toward self-organization can and often do produce larger-scale conscious entities.

Our resonance theory of consciousness attempts to provide a unified framework that includes neuroscience, as well as more fundamental questions of neurobiology and biophysics, and also the philosophy of mind. It gets to the heart of the differences that matter when it comes to consciousness and the evolution of physical systems.

It is all about vibrations, but it’s also about the type of vibrations and, most importantly, about shared vibrations.

And: Bone, not adrenaline, drives 'fight or flight' response.

Bone, not adrenaline, drives fight or flight response

- September 12, 2019

- Columbia University Irving Medical Center

- Adrenaline is considered crucial in triggering a 'fight or flight' response, but new research shows the response can't get started without a hormone made in bone.

FULL STORY

When faced with a predator or sudden danger, the heart rate goes up, breathing becomes more rapid, and fuel in the form of glucose is pumped throughout the body to prepare an animal to fight or flee.

These physiological changes, which constitute the "fight or flight" response, are thought to be triggered in part by the hormone adrenaline.

But a new study from Columbia researchers suggests that bony vertebrates can't muster this response to danger without the skeleton. The researchers found in mice and humans that almost immediately after the brain recognizes danger, it instructs the skeleton to flood the bloodstream with the bone-derived hormone osteocalcin, which is needed to turn on the fight or flight response.

"In bony vertebrates, the acute stress response is not possible without osteocalcin," says the study's senior investigator Gérard Karsenty, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

"It completely changes how we think about how acute stress responses occur."

Why Bone?

"The view of bones as merely an assembly of calcified tubes is deeply entrenched in our biomedical culture," Karsenty says. But about a decade ago, his lab hypothesized and demonstrated that the skeleton has hidden influences on other organs.

The research revealed that the skeleton releases osteocalcin, which travels through the bloodstream to affect the functions of the biology of the pancreas, the brain, muscles, and other organs.

A series of studies since then have shown that osteocalcin helps regulate metabolism by increasing the ability of cells to take in glucose, improves memory, and helps animals run faster with greater endurance.

Why does bone have all these seemingly unrelated effects on other organs?

"If you think of bone as something that evolved to protect the organism from danger -- the skull protects the brain from trauma, the skeleton allows vertebrates to escape predators, and even the bones in the ear alert us to approaching danger -- the hormonal functions of osteocalcin begin to make sense," Karsenty says. If bone evolved as a means to escape danger, Karsenty hypothesized that the skeleton should also be involved in the acute stress response, which is activated in the presence of danger.

Osteocalcin Necessary to React to Danger

If osteocalcin helps bring about the acute stress response, it must work fast, in the first few minutes after danger is detected.

In the new study, the researchers presented mice with predator urine and other stressors and looked for changes in the bloodstream. Within 2 to 3 minutes, they saw osteocalcin levels spike.

Similarly in people, the researchers found that osteocalcin also surges in people when they are subjected to the stress of public speaking or cross-examination.

When osteocalcin levels increased, heart rate, body temperature, and blood glucose levels in the mice also rose as the fight or flight response kicked in.

In contrast, mice that had been genetically engineered so that they were unable to make osteocalcin or its receptor were totally indifferent to the stressor. "Without osteocalcin, they didn't react strongly to the perceived danger," Karsenty says. "In the wild, they'd have a short day."

As a final test, the researchers were able to bring on an acute stress response in unstressed mice simply by injecting large amounts of osteocalcin.

Adrenaline Not Necessary for Fight or Flight

The findings may also explain why animals without adrenal glands and adrenal-insufficient patients -- with no means of producing adrenaline or other adrenal hormones -- can develop an acute stress response.

Among mice, this capability disappeared when the mice were unable to produce large amounts of osteocalcin.

"This shows us that circulating levels of osteocalcin are enough to drive the acute stress response," says Karsenty.

Physiology the New Frontier of Biology

Physiology may sound like old-fashioned biology, but new genetic techniques developed in the last 15 years have established it as a new frontier in science.

The ability to inactivate single genes in specific cells inside an animal, and at specific times, has led to the identification of many new inter-organ relationships. The skeleton is just one example; the heart and muscles are also exerting influence over other organs.

"I have no doubt that there are many more new inter-organ signals to be discovered," Karsenty says, "and these interactions may be as important as the ones discovered in the early part of the 20th century."

Story Source:

Materials provided by Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Julian Meyer Berger, Parminder Singh, Lori Khrimian, Donald A. Morgan, Subrata Chowdhury, Emilio Arteaga-Solis, Tamas L. Horvath, Ana I. Domingos, Anna L. Marsland, Vijay Kumal Yadav, Kamal Rahmouni, Xiao-Bing Gao, Gerard Karsenty. Mediation of the Acute Stress Response by the Skeleton. Cell Metabolism, 2019; DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.012

Cite This Page:

Columbia University Irving Medical Center. "Bone, not adrenaline, drives fight or flight response." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 12 September 2019. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/09/190912111018.htm>.